This has been a long time in coming and I keep putting it off and I continue to tell myself that it’s because I’m busy but I think the truth is that it’s my last words to her and they don’t feel perfect yet. I keep changing things and deleting things and adding stories and I feel like I’m not saying enough about her. Now, weeks later, the truth is I don’t think these words will ever be perfect.

Final words rarely are.

Clementine is a cocker spaniel that my wife and I have had the very great pleasure of being friends with over the last seven years. She traveled the country with us, made us laugh and watched us grow. In many regards, we owe Clementine a great deal because she was very much like a first child to us. We received her as a puppy, potty trained her and had to temper our schedules to meet hers.

She was our dog but she was also a member of our family in a very important way. My children loved her, my wife loved her, our friends loved her and I loved her. Looking back through my photos and memories, I see that Clementine is in many of them and she isn’t tucked away in a corner as an afterthought; she’s sitting on my lap, resting at my feet, standing by my side, a very prominent part of our lives.

Oh My Darling Clementine, you are lost and gone forever, dreadful sorry, Clementine…

*** *** *** *** ***

I never wanted to get a cocker spaniel. They always struck me as dopey looking, mangy animals. So, when my wife presented me with the idea of acquiring a second dog some 7 years ago, I adamantly fought against the idea tooth and nail. I wanted a dauschund or a Saint Bernard. I couldn’t tell which way my interests were leaning but I definitely wanted something with personality; something who’s actual physical attributes just popped out at you. I wanted a furry eclectic curio on four legs.

My wife persisted. She pulled up photo after photo of dopey looking, mangy cockers and said, “Look at this one! It’s beautiful! It’s like Lady from Lady and the Tramp!” and I’d say, “I’ve never seen Lady and the Tramp,” and she’d say, “What kind of sad and despicable childhood were you raised in?”

But she didn’t give up and I quickly became schooled in the history of the spaniel simply by proxy until finally, like the battered husband that I am, I caved and threw my hands up into the air and melodramatically moaned, “FINE! FINE! Let’s get the cocker spaniel!”

ABOVE: The lesson I learned was to make sure the doors were all shut before letting Clementine out of the bathtub.

One month later Jade and I found ourselves standing in the LAX parking lot with a small crate at our feet. Our visitor had arrived. The breeder told us that Sweet Pea (her name for our puppy) was the runt of the litter and just wanted to be held. “She just wants to crawl into your lap and be cuddled and snuggled,” the breeder would say via her weekly email to us. “I named her Sweet Pea because that’s what she is – just a darling little Sweet Pea – the most adorable personality. You’ll love her.”

We’d seen photos of her online but nothing compared to the moment when we opened her kennel door and little Sweet Pea hesitantly stepped out, afraid of the world. I sat down on a curb stop and watched as this little fuzzy dot crawled out into the California sun after flying straight through, all alone, from Florida.

ABOVE: The very first time we met little Clementine. Her very first picture with us.

She hesitantly peeked out, a big white ball of fuzz with brown splotches, looked around with the world’s saddest eyes, slowly walked over to me in the teeniest, tiniest little steps, hopped into my lap and laid down. She was the most adorable puppy I’d ever seen in my life and I just wanted to pet her and squeeze her and hold her and keep her. From that moment on I couldn’t imagine having gotten any other dog besides a cocker spaniel. We told her that her name was Clementine and from that moment on, she owned our hearts.

ABOVE: Our little vampire would nibble on your toes with those sharp fangs.

Clementine was born with the absolute friendliest demeanor you’ve ever seen in an animal and even in her later years she had the attitude and spirit of a puppy. She simply exuded joy.

She was a terrible guard dog and would bark at her own farts. She was as dumb as a box of rocks and would lose in a fight every time but she the one thing she was good at, she was great at. She was the type of dog that loyalty speaks of in its truest sense.

She really was so very, very stupid but so very, very respectable. In my opinion, personality will win out over intelligence every time (and that rule applies to both animals as well as humans).

She was a very simple animal to love.

In fact, some of my fondest memories of her are simply driving in the car, she resting on my lap while America’s countryside passed by. She and I saw quite a few states just like that.

SOUTH DAKOTA

MONTANA

UTAH

COLORADO

I always loved taking a break and escaping to the dog park with her for a bit. I’d let her off the leash and she’d wander away and get lost and not be able to find her way back to me. Meanwhile, I’d just sit on a picnic table and watch her sniff around, unable to pick up a scent and now, writing this, I see how horrible that would actually become. Eventually, she’d simply give up and stand by some new owner. She would simply insert herself into a new family. That said…. perhaps loyalty to ME was not her best attribute so much as loyalty to the human race… or mankind… or The Cause… or Joy. She was just very stupid and lovable.

ABOVE: The park in Denver where I proposed to Jade. We revisited it with the dogs on a vacation passing through CO.

One of my final memories of her was taking her for a stroll with my children and teaching them how to walk her; me trying to teach them to gently nudge without yanking her around. I’d hand Rory the leash and he’d walk her and then I’d hand Quinn the leash and she’d walk her. All by themselves. As we neared our home I told Rory to go run with Clementine. “RUN!” I shouted as I watched the two of them scramble down the sidewalk side by side before disappearing into our driveway.

A moment later Rory jumped out from behind the fence followed directly by Clementine and I always imagined that they would somehow be really great friends for many, many years – a boy and his dog. The idea always seemed very romantic to me.

ABOVE: Baby Rory and Clementine.

ABOVE: Baby Quinn and Clementine.

ABOVE: Little Lady Quinn and Clementine at a family campground.

*** *** *** *** *** *** ***

Last Wednesday night my family went out to a little place called Jerry’s Pizza for dinner. We just wanted to get out of the house and so we loaded everyone up and took off. Before I left, last one out the door, as per usual, I checked to make sure the back doors were locked, Clem had water, the stove was off, and then I reached down and rubbed her nose and said, “See you in a bit, Clemmie. Be good. Good girl.”

And then I walked out the door.

And then we ate pizza.

And then we came home and kicked open the doors.

And then I sat down to do some work.

And then around 10pm as I was feeding Clementine, I realized I hadn’t seen her for some time.

We have a completely fenced in yard and so it is not unnatural for us to kick the doors open and let Clementine take rein of the property. That said, over the course of the last few years that we’ve lived in this house, she’s gotten out a handful of times BUT each time, by the Grace of God, she has made her way back home, typically by Jade or I finding her or by the hand of a gentle stranger. Again, Clementine will go to strangers. She will get in their cars. They don’t even need candy. They just need to ask. She will adopt herself into their lives. Thankfully she wears a collar with our contact info and most people are kind enough to heed it.

SIDE BAR: IF YOU ARE A DOG OWNER, GET A COLLAR WITH YOUR CONTACT INFO ON IT. When I see a dog walking around without a collar or without plates, I think of all the times my dog has gotten away and I just shudder. GO. NOW. TONIGHT.

I called her name a few times and hit all of the standard hiding places; under the bed, under the couch, under the desk. Sometimes she just hides. This is not abnormal. Sometimes you think she’s gotten out but really she’s just lying under the couch and doesn’t feel like coming out.

I find nothing.

I walk outside and all the gates are closed and locked. I call her name. Nothing. I walk into the street. Nothing. I walk down the block, calling for her. Nothing.

She’s gotten out before. I know that panicking doesn’t help. I force the rising knot in my stomach to untwist. I try to run through the emotion and get straight to the logic.

I walk around our block, one of those huge city blocks that is the size of three normal blocks. I walk into the next neighborhood. I get in my car and drive around. I come home and Jade leaves to try her luck – keep in mind that the children are asleep so we can’t fully abandon the house. In this state of, “I want to go find my dog,” one of us is always forced to plant our feet at the house and it makes us both incredibly anxious.

So I pace.

Twenty minutes. Thirty minutes. Forty-five minutes. Ninety minutes. Nothing is turning up and it’s getting late. This has never happened before. She’s never not come home. We’ve never had to go to bed without her in the house. She’s never done this and I feel so helpless. I suddenly realize how big the world is. I can suddenly see how massive everything is. My dog is missing and she could be anywhere. Any backyard. On any street. In any neighborhood. With each passing moment she could be getting further and further away and I don’t even know it. Blocks are turning into miles. She’s leaving Van Nuys… into Panorama City… crossing a busy street. Traffic is flying by. Horns are honking. She’s scared.

Or she could be coming closer! And so I call her name again but there is no response and, ultimately, Jade and I go inside. And we go to sleep. Because, frankly, we don’t know what else to do and now, today, I regret that decision. I regret it horribly and painfully. I hate that I stopped looking. Knowing what I know now I wish that I had just kept going and kept going and shouted longer and louder and looked harder and driven further.

But we didn’t.

And that night I have a dream that Clementine is returned to us and I’m hugging her and smiling and laughing and when I wake up in my bed I’m so happy that everything is over and that Clem is back, our little Sweet Pea is back, and then I remember that she isn’t here and we haven’t found her and that it was a just dream and I’m heartbroken again.

ABOVE: Road trip to Montana. Clementine was very wonderful to snuggle when she was clean.

Jade goes to Staples and makes fliers. White ones. Hangs them up on telephone lines. She makes a huge poster and hangs it on the front of our house so anyone walking by can see that she’s missing. She calls shelters and animal hospitals but no one has seen a cocker.

This, of course, is GREAT NEWS because we know she isn’t hurt or dead. There has been no confirmation.

But, worse than that… we have nothing. We have no idea.

Jade says, “I just spoke to Tiffany and she says that some people find nice dogs and kidnap them and try to sell them,” and I say, “BASTARDS!” and Jade begins to scan Craigslist for people selling cockers. She finds one and, when she asks to see a photo of the dog, the man deletes the posting and I think Clementine has slipped away from us for good. I become positive that the man has my dog and that she’s in his house. I wonder if she’s in a cage or on his couch. Is he treating her nice. Does this guy live on my block? In my neighborhood? Could Clementine be so close? OH, IF I FIND THAT GUY I’M GOING TO BREAK HIS WINDOWS!

Jade reads on a lost dog forum that in order to achieve higher visibility, fliers should be bright pink or orange because they attract the eye. People tend to look past white ones. So Jade goes back to Staples and prints off another hundred fliers and she covers our neighborhood with them. She puts them under windshield wipers and on light posts and she hands them to people and she talks to strangers and, meanwhile, I’ve got an edit that’s due the next day and am working and I hate it.

Rory and Quinn, my three year old twins, stand in the front yard and, whenever anyone walks by they say, “Have you seen my dog?” and the people smile and shake their heads and walk away. Someone else walks by and they say, “Excuse me? Have you seen my dog?” and they smile and shake their head and walk away. Rory shouts, “She’s white and red! She’s lost! You go find her!” and then the person is gone and I wonder if my son feels as helpless as I do, trapped in a yard.

I get angry at Clementine and I say, “Stupid dog! What are you leaving the yard for! Where were you going? Where are you?” and then somebody tells us about Pitbull bait and how dogs that are in dog fights need to train and so lost and found dogs are sometimes used as bait and I shut my eyes and try to wash the image of Clementine being torn to pieces by a dog and his asshole owner but I can’t.

That night Jade goes to sleep and I’m still working, the front door hanging open. I go outside on a whim, hoping to just see her prancing down the street towards our house, back from her big adventure. My brain doesn’t accept that she’s gone and I just expect her to…. be back. I shout her name.

Nothing.

A Latino couple walks up to me and the woman says, “We lost our cat,” and I say, “Yeah,” and she says, “Your dog was beautiful and so friendly. A lot of people would find a dog like that and keep it. Take it home for their kids. So friendly,” and I imagine these people picking up my dog and I imagine Clementine in their house on my very block, loving her and feeding her and playing with her. BASTARDS!

I vow to get her back. I’m going to find the selfish pricks who think it’s okay to steal dogs and I’m going to get her back. And when I find the guy who did this I’m going to kick the shit out of him. Or I’m at least going to try because some things are just worth getting your nose broken over. I’m hurt and angry and heartbroken. She’s part of my family and my house is feeling like a puzzle piece is missing.

I love my dog and I miss her and I WANT HER BACK!

Last year we put our older dog to sleep and we grieved fiercely over her loss but there was preparation and peace surrounding the process. This was just chaos and confusion and neither of us knew what to feel or what to expect.

That night I go to sleep and I dream again that Clementine has returned and the next morning I awake and I begin to feel the very real twinge of loss setting in. Could she be gone? Really gone? Truly gone? My heart pushes the possibility aside, unwilling to accept. I get up and tell myself that someone will bring her back. Someone has her and they’ll bring her back.

A woman emails us, someone who saw the Craigslist ad that we posted. She tells me her neighbor stole her dog and kept it hidden for three months until she put up a $500 reward. BASTARDS!

We put up a $500 reward.

Nothing happens.

ABOVE: Waking up at a truck stop after a night of sleeping in the car with these two.

That night at dinner we get a phone call from a stranger. They say they’ve seen our flyer and they’ve seen our Clementine just last night one block from our home. I immediately drop my fork, grab my keys, jump in my car and head into the setting sun. I stop in the parking lot she was allegedly last seen in and scour it top to bottom in complete desperation. I call her name. I shout. I walk for blocks. I jump back in my car and drive and shout and nothing. The sun is gone. It’s dark. I go back home. Every time I turn back I feel like I’m quitting.

I walk in the door and I can see on Jade’s face that she’s hoping and expecting me to walk in with our dog. It’s the first solid lead we’ve had and now it’s dead. I shake my head and her shoulders fall.

If you’ve never loved a pet, a part of your soul has not lived.

We eat dinner in silence and then Jade takes the car out to look while I get the kids ready for bed. She returns empty handed.

ABOVE: This is her excited face.

That night we decide to start a Facebook page called FindClem. If someone is keeping her or trying to sell her, we’ll just make her so internet famous that they’ll get busted. We’ll create an enormous viral campaign. Clementine has a face made for radio – just a droopy, mangy maw and I became convinced that people would help us. I stand in my kitchen and say, “We’ll blow this thing up! We’ll get her back! We’ll make t-shirts! Stickers! Tweets! We’re going global!”

We never go global but over the course of the following 24 hours we amass a total of just over 100 likes, mostly from complete strangers. People emailed us and personal messaged us with links to cockers that fit Clem’s description being sold online. IS THIS YOUR DOG? DID I FIND CLEMENTINE? LOOK HERE!”

None of them were her but it was inspiring to see such help rally in such a short time span.

We go to sleep.

In the morning my friend texts me and says he had a dream that we found Clementine and that she was hiding under a car.

We take our fliers and we head back out into the street. Rory and I walk down one side of the block while Jade, Quinn and Bryce walk down the other as we begin to canvass East. We hand fliers to everyone we pass. We hang them up on pegboards in restaurants.

When we reach the end of the road we turn around and my anger rises every time I see one of the hot pink MISSING posters lying in the gutter. These are my hopes that people are discarding, throwing on the ground. My fury peaks when I see that people have intentionally ripped them off several light posts. For every good person out there it seems there are two or three awful ones… maybe more.

We meet back at the car and, in a Hail Mary move, decide to try one more place – the bridge across the street. We hit the walk button. We pass over the crosswalk. We approach a man fixing a bicycle. I hand him a flier and say, “Lost my dog,” and he looks at me and looks at the flier and he stands up and he smells like alcohol and he points at Clementine and he says, in a thick Spanish / drunk accent, “This your dog?” and I say, “Yes. Yes. Have you seen her?” and he says, “I seen this dog,” and everything in me blooms. Hope. Fear. Anxiety.

The man, whose name I later learn is Carlos, reaches into his back pocket and pulls out a collection of hot pink Lost Clementine fliers. Maybe 20 in all. Jade says, “Why do you have those?” and Carlos points to the dollar signs on the poster and says, “Is there a reward?” and I say, “There is a reward for the dog, yes, yeah,” and he says, “Is there a reward for information leading to the location of your dog?” and I say, “There is a reward for my dog,” and he says, “I have your dog.”

ABOVE: Brookbank Christmas card 2013.

Jade and I both look at each other and my stomach flip-flops and Jade says, “Where is she!? WHERE IS SHE?!” and he points back to the money and I say, “Show me where she is,” and he says, “Come here… I show you…” and I tell Jade to stay with the kids and I turn and I follow this stranger down the sidewalk as he takes off at a brisk pace.

As I jog to keep up with his Goliath steps, he glances over his shoulder and casual states, “I live out here, you know? That’s my home. I live on the street,” and I nod silently as he points back to his bicycle. Half a block later he stops at the crosswalk and says, “Here,” and I look around. I say, “What?” and now I feel like a fool. I’m letting a drunk man lead me around as I stupidly follow blind hope.

He says again, “Here,” and then, “Friday night. I saw that dog running around right here. I thought to myself, what a beautiful animal. I used to have a dog like that when I was a boy. A cocker spaniel. White and spotted like a cow. Beautiful dog. I thought… that dog is lost. I came to pet it and it ran back and forth and before I got to it…. it jumped into the street and was hit by a car and was torn into two pieces. I’ve never seen anything like it before.”

This is the part of the story where my stomach drops to the floor and I stand up straight and I can feel a nervous breakdown beginning to grow and I lean in and I say, “What? What’s that?” and he says, “I’ve never seen anything like it before. A car ran her over and tore her in half. She was so beautiful but she was a mess,” and I say, “My dog was….. hit by a car?… and you saw this?”

He says, “Here… look, look. Follow me,” and he marches into the busy traffic, nearly a third of the way across the street. He says, “Right here. This is where she was,” and then he walks back while he points at the ground. I look down and see what looks like a tire burn out. I say, “What is this? What? The tire mark?” and he says, “No. That’s no tire mark. Your dog was hit there-” and he points to the spot as I watch a half dozen tires run over that exact place, perfectly aligned in the street.

He says, “I couldn’t leave her out there. I was drunk. I went out and I picked her up. All of her pieces. All of her insides. And I dragged her,” and he points to the tire skids, “over to here,” and he steps down into the gutter a points at a blotch of dark black matter. I look at the mark in the center of the road and I look at the smudge in the gutter and I look at the skid mark connecting them and I say, “That’s…. her blood? That tire mark is her blood trail?” and he says, “Yes! It was terribly sad! And I couldn’t leave her here. She was too beautiful. So beautiful! So I scooped all of her pieces up and I carried them across the street and I put them in that garbage can.”

He points across the street to a garbage can I’ve walked past at least a dozen times since losing her. “No…” I think. “Please don’t let that be true. Not like this.”

He begins running across the street, saying to hell with the traffic light. He cuts between speeding cars and my hands are starting to shake. We approach the garbage can and he says, “I put her in here but it was just… so much,” and I say, “So much what?” and he says, “I didn’t want anyone to see – children or people – she was -” and he grimaces and rubs his fingers together, never completing the thought. “So I cut the bag out of the can — you see here — you see where I cut it?” and sure enough there is a bit of black torn plastic left inside the now empty garbage can.

I don’t want to believe anything he’s saying. I’m certain he’s drunk. I’m certain he’s crazy. I’m certain he’s just a violent and horrible man who wants to tell me lies and he’s making it all up and nothing is true but I follow him and I listen to him and I can’t stop because I have to hear it all.

He says, “This way. I took her over here… in the bag…” and he takes me to a dumpster about twenty yards away. He says, “Here. She’s in here. Now.”

And I bite my tongue and I bite my lip and I rub my hands on my pants and my knees are weak and I can see Jade watching me from across the street and I say, “My dog is in this dumpster?” and in my head I’m thinking, “My Sweet Pea is in this dumpster? My baby that crawled into my lap at the airport? My precious Clementine is IN THIS DUMPSTER LIKE A PIECE OF TRASH!?”

Carlos says, “Yes,” and then hops in and starts pulling boxes out and pushing things aside. He finds black trash bags and pokes them and prods them and moves them around before he says, “I smell her.” He lays his hand on a bag before quickly pulling it back and says, “This one…” and I look at him and I say, “Open it,” and a fear comes over his face that makes me wonder how bad it all was. He says, “You serious, man?” and I say, “I need to see her. I need to see my dog,” and he bends down and sticks his finger into the bag and tears it open and yellow ooze pours out and I look away but it’s just rotten restaurant food.

He says, “She’s not here…maybe they emptied the trash,” and I think, “Or maybe you made the whole thing up to get money,” and then The Logic in me speaks up and says, “There are too many compelling facts. The mark in the road. The fabric on the garbage can. The fact that the story was so quickly fabricated and told in such detail. The location of the event to the parking lot from the previous call.”

I don’t want to believe it and so my heart cries liar.

Carlos and I cross the street as Jade approaches us. I say, “Jade, this gentleman is alleging that–” but Jade, with red eyes, cuts me off and says, “I know. I just heard. His friends told me,” and she points to a group of rag-tag homeless men that are halfway to oblivion well before noon.

A man on the street says he was there as well. Says he saw it happen. But my heart still disagrees and won’t process it. Not Clementine. Not like this. Not my Clementine. She’s too sweet. Too precious. Too little. I’m still picturing her in someone’s living room, eating popcorn with them while they watch a movie.

ABOVE: An art installment at an abandoned desert museum.

I leave Carlos behind and approach another homeless person on the block. I ask her if she knows Carlos and she says, “Yeah,” and I say, “What do you think of him? How is he?” I feel like I need to know what the personal integrity of this man is, which just seems crazy. Anything to prove him wrong. How did my day end here? How did this all happen? I’m so angry that I ever suggested going to Jerry’s Pizza. I count all of my decisions back and try to figure out how this could have been avoided. My thoughts are interrupted by Jean, the homeless woman, “He’ll lie and cheat to get what he wants. He ripped my friend off twice for more than a hundred bucks.”

Is this man some kind of con artist that has hatched a story just in case he came across us, my wife and I, suspecting that we’d be looking in the neighborhood? Is he telling me the truth? If he saw my dog die and thought he could make money, why didn’t he try calling us off the number on the fliers? Why was he collecting all of our fliers? He says it was so people wouldn’t waste time searching for a dead dog. Or maybe it’s because he didn’t want other people to be conscious of the reward money.

I walk home, jaded and confused. I try to separate logic from emotion, an act that has been nearly impossible over the last hour. My brain and my heart are telling me two different things. Inside, Jade and I discuss what we’ve seen and heard. I tell her that I don’t know what to believe and she agrees.

Forty-five minutes later I go back to the intersection and stare at the streak and try to imagine Clementine but I can’t. I see Carlos staring at me but I ignore him. I look at the garbage can and I look at the dumpster and my heart breaks open.

I walk home and I tell Jade that I think Carlos is telling the truth. I tell her that my brain is saying it all makes sense but my heart is unwilling to accept it. She nods and her eyes gloss over with tears for our little Clemmie.

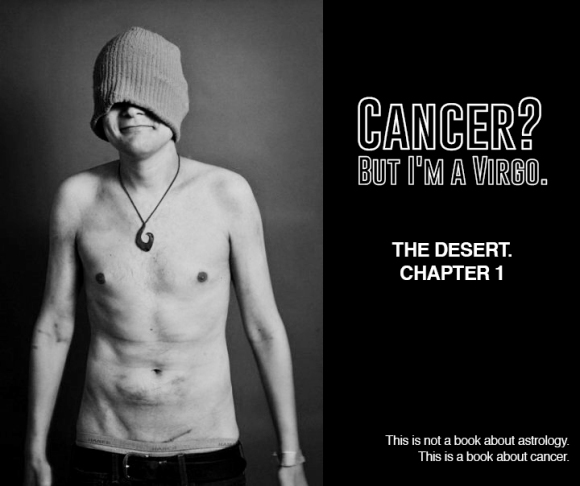

ABOVE: Clementine getting cozy with cancer-era Johnny.

That evening we log onto our FindClem Facebook page, our beacon of hope, and create a post that reads, “The saddest of days in The Brookbank Home as we discovered today that our very dearest Clementine is no longer with us. Thank you so much to everyone that helped and reached out. We appreciate you all.”

After typing the words, I just stare at them for a moment as the pieces and the truths all fall into place for me.

All the dark and disgusting things that have been in my heart, all the fear and despair that I’ve kept mostly at bay are creeping towards the surface. The Black Abyss that has been circling me like a mist is getting thicker. Typing the words has brought this dormant thought to activation but it isn’t until I hit enter that I realize it’s true. And in that truth I understand the certainty that Clementine is gone. Forever. I realize that I will never see her again. I realize and understand that I will never pet her again. I will never take her to another dog park. I will never go on a vacation with her ever again. I’ll never wake up to her curled up on my feet and I’ll never get to watch my children chase her again. She’ll never greet me at the door. She’ll never see me off. I’ll never get to take her on another walk.

Ever.

Again.

The RETURN key clicks and the post appears for the world to see. It’s broadcast in front of me like a fact and everything that has held on for the last three days let’s go; breaks like a levy. I stand up and I walk to the corner and I fall against the door and I simply weep into my hands for the loss of my friend.

The anchor of hope is gone and it’s been replaced by a weight of bricks tied to my neck and I can feel it pulling me down and making me sick. I want to lash out but there’s nothing to grab. Jade puts her hands around my waist and sobs into my shirt. And it goes on and on and on.

It’s not right. None of it is right. Clementine getting out of the fence was mischievous and stupid. Clementine getting hit by a car was, frankly, just bad luck. But Clementine being picked up by a drunk man and disposed of in a dumpster…

It’s not right and she deserved better.

*** *** *** *** ***

We’re just over a week out from her death and I still find myself reacting to muscle memory. In the morning I go to feed her and when I have leftovers from dinner my first reaction is to just toss the scraps on the ground. Before I go to bed I catch myself just before I shout, “Bedtime, Clem! C’mon!” Sometimes I think I hear a scratch at the door and, just because I believe in miracles, I go and check… but it’s never her.

I hear dogs barking in the street and I always pause to listen for her voice… but it’s just strange canines that belong to other families.

We’ve picked up her bed and have begun the process of de-dogging the house – giving away her bag of food and putting away her toys. I pulled the cover off her mattress and threw it in the laundry basket only to have Jade call me back a few minutes later. I rounded the corner to find her holding it out to me.

She says, “I’m going to wash this,” and I say, “Okay,” and she says, “Do you want to smell it? This is all we have left,” and I am suddenly faced with this goodbye that I wasn’t at all ready for. I grab the stupid dog blanket and I shove it into my face and I inhale and I can smell her.

One last time.

ABOVE: The very last photo taken of her with my youngest daughter Bryce, just a day or two before she disappeared.